Chris Gratien, Georgetown University

Due to the staggering number of languages used within the Ottoman Empire, not to mention the many different states with which the Ottomans had diplomatic ties, scores of translators were employed at the various levels of government, and job requirements for translator or official positions sometimes asked for knowledge of 3 or more languages. Thus, the Ottoman state in its decentralized form was able to facilitate reasonably effective communication with a very linguistically heterogeneous population.

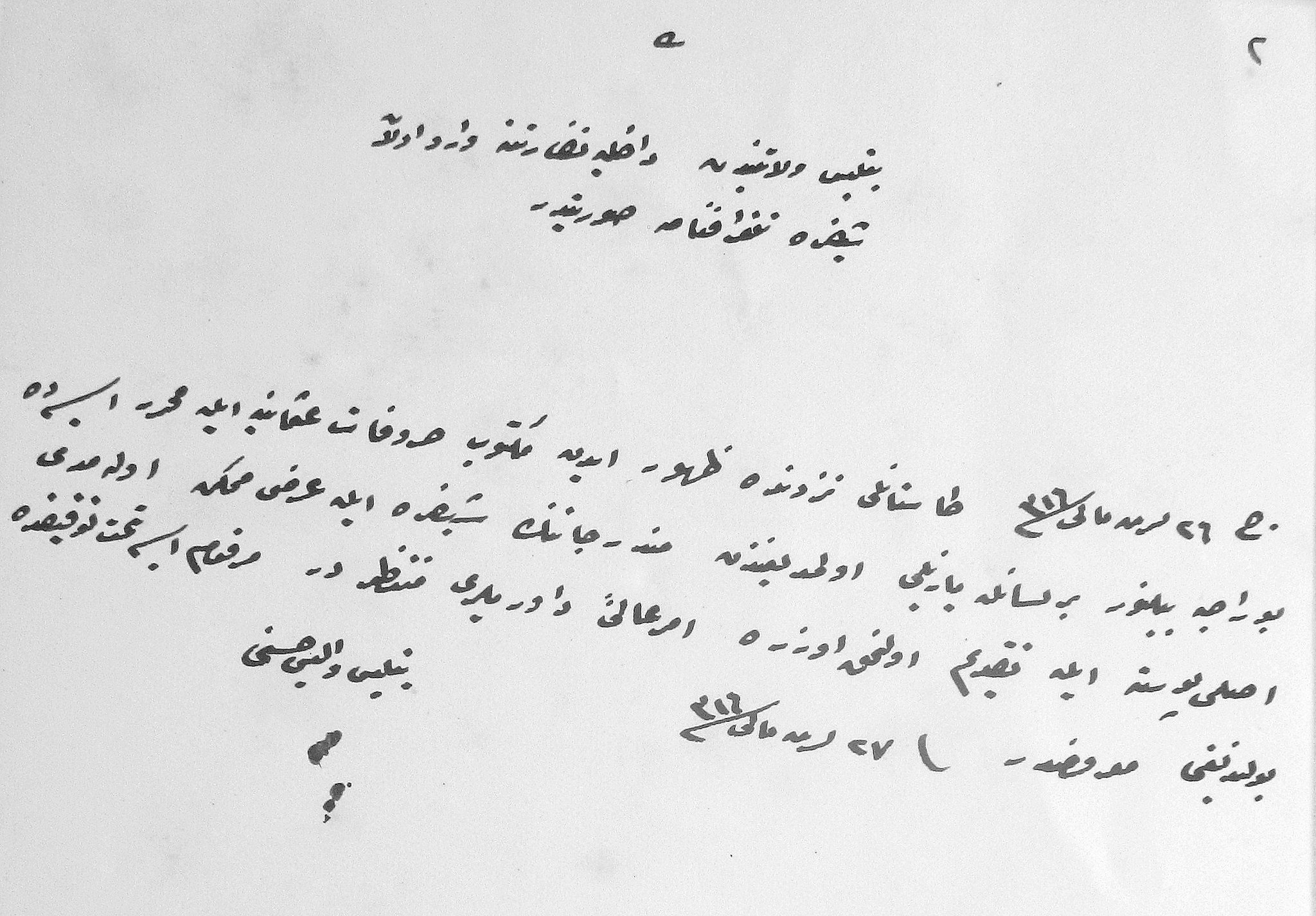

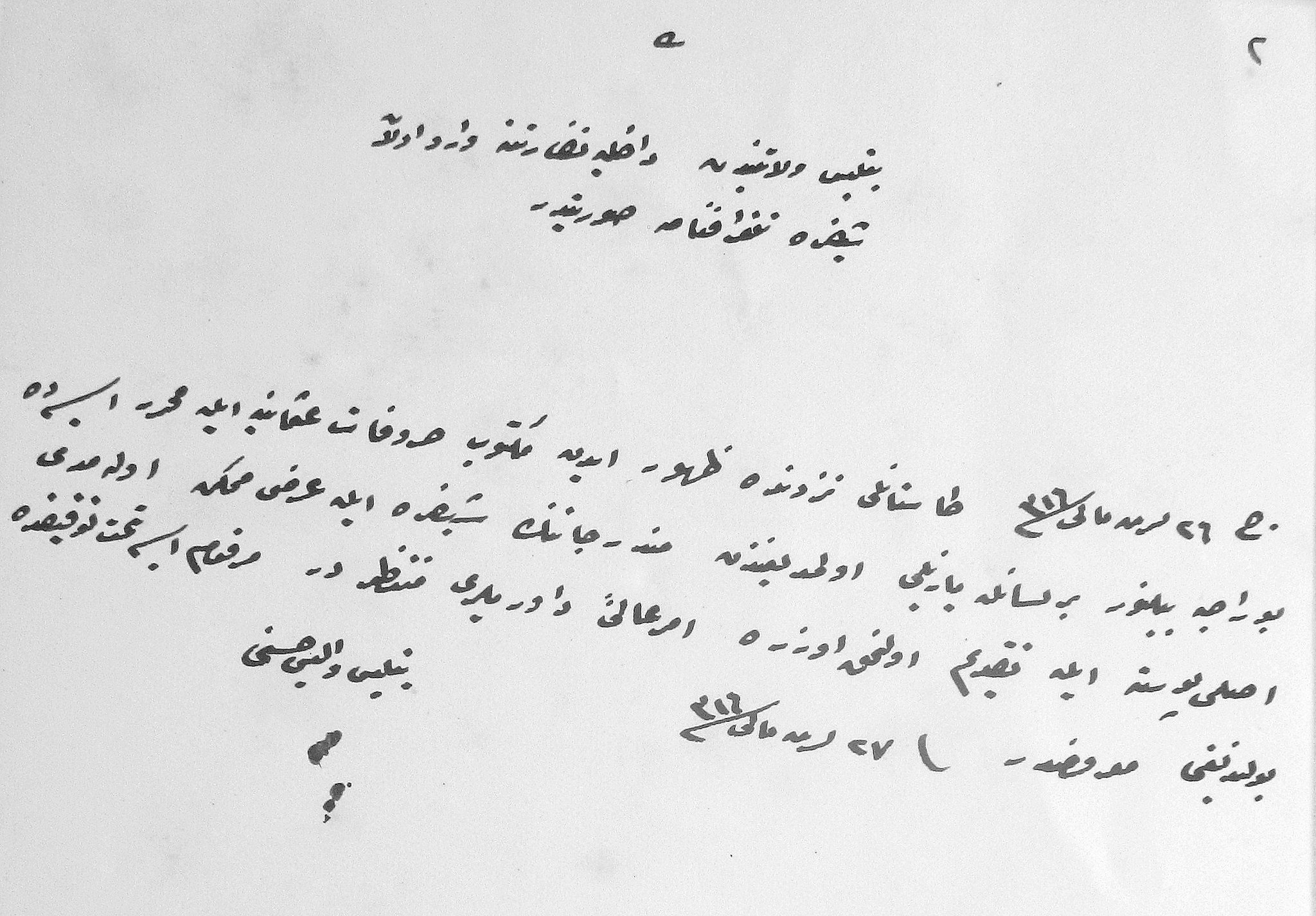

Yet, this document from 1900 illustrates just how diverse the languages of the Empire were. It is the transcription of a telegraph from the Governor of Bitlis to the Interior Ministry regarding an indecipherable letter originating from Dagestan (Dağıstan) in the North Caucasus. He writes, that "although it is written with Ottoman letters, it was not possible to transmit the letter with an encoded telegram because it is written in a language unknown here [i.e. in Bitlis]." Thus, it was necessary to submit the letter the old-fashioned way by post.

Unfortunately, I was unable to track down the original letter, but we can guess what sort of language it might have been. We can rule out Arabic, Persian, and Kurdish, because these would have been known to the translators. Other languages were also sometimes written using the Ottoman alphabet, such as Albanian, but given the location in Dagestan we should presume that it was either Circassian (Adyghe/Çerkez) or Chechen, which were sometimes written. It is possible that the letter could involve Muslim refugees from the area, of which thousands came to the Ottoman Empire. Of course, there were and are far too many languages spoken in the Caucasus to be sure.

BOA Y-PRK-DH 11/63 (17 Şaban 1318)

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteCould it be the Roma Ubykh tounge. See: "Crimean Roma - legend and Folklore" V.Toropov, 2009

ReplyDelete"After the Black Sea Caucasian coast was taken by the Russian Empire in 1864, the new authorities banned Muslims from living in the coastal area. As a result the Ubykh community, that had been rather strong (74,500 people by contemporary data) and that had been living in the area around what is now the city of Soči, was forced to re-settle into the Ottoman Empire. Less than 130 years had passed since then; no more than five or six generations of the Ubykhs had succeeded each other, and Ubykh language disappeared completely. This sad event happened in October 1992, when the last bearer of this tongue died in Turkey. As for the current level of preservation of Romani language by the people whose ancestors moved from the Crimea to the Ottoman Empire in the mid-19th century, the Russian Roma scholars have no reliable information. The story of the Ubykhs‘ tongue decline is noteworthy as proof of the fact that even a language of a rather large ethnic group may not last long if its bearers do nothing to support it. Still let‘s make some comparison between the history of Crimean Roma speech and that of the Ubykhs. The Ubykhs, who were all Muslims, were scattered across the Ottoman Empire; the Roma, who were equally disperse in the Crimean Khanate, had to accept Islam in order not to be treated with contempt as ―infidels,‖ as well as to enter the Muslim society with a minimum of obstacles."